Readers must familiarize themselves with these subtopics to understand the concepts discussed in this chapter. These articles are linked within this chapter, but it may be easier to read them in advance.

Where are the Amphibians? - armies need amphibious vehicles

The ERGM/LRLAP Fraud - gun-launched guided missiles fail

Bunker Barges - the best way to move fuel ashore

DE Corvettes - stealthy coastal ships

MK-71 8-inch Naval Gun - three times more firepower

LCU Gunboats - an excellent shore bombardment combo

Ship Counter-Battery Radar - incorporate proven technology on ships

Bait Ships - use old ships as decoys

Landing Ship Assault - a modern LST is vital

Thoughts on Seabasing - good and bad

Dysfunctional Amphibious Ships - US Navy faux amphibs

Vital Amtrack Variants - 120mm mortars and SPAAGs

_________________________________________________________

Types of Amphibious Operations

Military experts sometimes proclaim that major amphibious operations will never be conducted because they are too risky and bloody. With that attitude, the Allies would never have won World War II. What if Iran overran Kuwait and nearby Arab nations refused to allow American troops to land? Would Generals tell their American President that there is nothing the massive US military can do because amphibious landings are too dangerous? During World War II, the US Army conducted more large amphibious operations than the US Marine Corps. Unfortunately, the Army's long-time infatuation with massive Soviet armor battles erased institutional memory. Some soldiers have suggested that large airborne operations are more effective, but only if you ignore logistics and modern air defense weaponry.

The United States has not

conducted a major amphibious operation since the Korean war, so deep thinking about amphibious operations is rare. The

US Marine

Corps itself never conducts realistic training for anything

more than a 2000-man landing force. As a result, amphibious warfare

doctrine has devolved into "Operational Maneuver From The Sea" (OMFTS); a

confusing sales pitch for new weaponry that is fundamentally wrong.

Recently, the term "Ship-To-Objective Maneuver" (STOM) has been used

because it forms a meaner acronym. Before discussing doctrinal flaws, we

must review the seven types of amphibious

operations:

The United States has not

conducted a major amphibious operation since the Korean war, so deep thinking about amphibious operations is rare. The

US Marine

Corps itself never conducts realistic training for anything

more than a 2000-man landing force. As a result, amphibious warfare

doctrine has devolved into "Operational Maneuver From The Sea" (OMFTS); a

confusing sales pitch for new weaponry that is fundamentally wrong.

Recently, the term "Ship-To-Objective Maneuver" (STOM) has been used

because it forms a meaner acronym. Before discussing doctrinal flaws, we

must review the seven types of amphibious

operations:

Amphibious Demonstration - a feint to confuse the enemy

Naval gunfire is used, landing craft are put in the water and head for the beach, and helicopters may simulate landings. Forces don't hit the beach or the LZ, but turn back to their ships and land elsewhere to reinforce the actual landing. This was used several times by the Marine Corps during World War II so Japanese commanders would commit forces in reserve to the wrong areas, and partly during the 1991 Persian Gulf war to keep Iraqis in their coastal defenses.

Amphibious Envelopment - a flanking movement where no ships are needed

Landing craft or boats pick up units ashore and ferry them several miles to envelope an enemy. The US Marine Corps can employ this tactic by using its amphibious vehicles. The key factor is that waterborne craft must swing far enough into the ocean or lake to avoid enemy shore fire. This may be done in coordination with a major ground offensive and the landing force may rely on land-based aircraft and artillery for fire support. This was used several times in the Pacific theater during World War II, and is described in the famous novel "The Naked and the Dead." Iraq tried this early in the 1991 Persian Gulf war, but the creative idea was smashed by airpower.

Amphibious Raid - a seaborne strike by units landed by boat or helicopter

This is used to quickly destroy enemy facilities and collect intelligence. The raid force may range from a 40-man platoon to a 4000-man brigade, which withdraws before a counterattack can be organized.

Amphibious Seizure - secures a small objective isolated from major reinforcement

This is often an island, but sometimes an isolated airfield or ship anchorage, like Guadalcanal in World War II. Since the objective is isolated there is no need to rapidly push inland or seize a port for the off-load of heavy ground forces from large transports to continue an offensive inland.

Amphibious Probe - the seizure of a lightly defended area to test the reaction of enemy forces

This is used to lure an enemy out of hiding and to judge his strength. It is normally a light battalion-size force to allow rapid withdrawal should the enemy counterattack in force.

Amphibious Invasion - opens a port to allow the rapid offload of large forces as part of an offensive inland

This is the largest and and most complex type in which speed is critical to allow the rapid employment of large follow-on forces to exploit the strategic surprise. The seizure of a seaport is the main focus.

Amphibious Withdrawal - evacuates fleeing ground forces by sea

The best known are the British at Dunkirk and US Marines at Hungnam in Korea.

Doctrinal Heresy

These seven amphibious tactics seem logical, however, the guardians of amphibious warfare doctrine may object because they never recognized Amphibious Envelopment. Since this tactic is not officially listed by the US Marine Corps, many officers will never consider it. If a bright officer proposes using boats to outflank a ground force, senior officers may scoff at a concept they have never been taught or practiced. This should not be confused with a large Amphibious Invasion used to outflank an enemy, like the landing at Anzio in Italy during World War II. That was a huge force embarked on ships to conduct a major invasion that required intense planning and coordination. An Amphibious Envelopment is a simple affair in which small craft ferry soldiers or marines around a flank. Armies need amphibious vehicles for this tactic, and for river crossings, operations in marshlands, and expeditionary operations where no port is available to off-load.

Another unrecognized tactic is the Amphibious Probe, which takes advantage of the greater mobility offered by helicopters and the precision striking power of modern aircraft. Enemy forces often find it impossible to defend their entire shoreline so they form powerful mobile reaction forces. If the amphibious force has air superiority, defenders remain hidden until an amphibious landing is identified and a counterattack ordered. Therefore, an amphibious plan may employ a probe in which a modest force seizes a weakly defended landing point to test an enemy's reaction. If the enemy moves to counterattack, it is pounded by air strikes while the probe becomes a feint as the landing force withdraws. If the probe is ignored, a much larger amphibious force may be landed as part of a full invasion.

In many cases, an amphibious force is too small to invade so a probe can be used to distract an enemy and divert his resources from operations elsewhere. For example, when 12 of North Vietnam's 13 army divisions were committed to the invasion of South Vietnam in 1975, the US military suggested landing a US Marine division on the coast of North Vietnam. This was far too small to push to Hanoi, but the North Vietnamese would not know its true size and it could threatened supply lines and disrupt plans for the entire North Vietnamese Army. The Amphibious Envelopment and Amphibious Probe must be recognized in manuals and taught and practiced in peacetime so officers will be acquainted with these options.

A bigger issue the guardians of doctrine may dispute is the division of the traditional category of "amphibious assault", which is now defined as: "a prelude to further combat operations ashore; to seize a site required as an advanced naval or air base; or to deny the use of the site or area to the enemy." This is confusing because it fails to describe a clear mission, and "assault" is a poor term because it reminds everyone of bloody beach battles of World War II in which soldiers and marines charged through fortifications on foot. As a result, any recommendation for conducting an amphibious assault is met with disdain by most Generals and politicians. Second, "assault" fails to distinguish an invasion from a seizure. This led the US Navy and Marine Corps to adopt an unrealistic concept for future Amphibious Invasions.

OMFTS is Flawed

Since the US Navy is concerned about sea mines and shore-based missile threats, the US Marine Corps accepted a concept of offloading ships from "over-the-horizon," which is about 20 to 100 miles offshore. This OMFTS concept seeks to fight an enemy safely from the sea without quickly securing a port for the entry of larger forces or moving logistical support forces ashore. This is effective for counterinsurgency operations where a lightly armed enemy is widely dispersed in small units. However, it remains impractical for an Amphibious Invasion for several reasons. First, the Navy's current 5-inch guns lack the range to fire more than 13 miles. Plans to use new ultra-expensive GPS-guided "ERGM/LRLAP" gun-fired missiles are ludicrous. A newer proposal for a 155mm naval gun to fire small, expensive missiles with just a 24 lb warhead 100 miles remains an impossible fantasy.

In addition, unarmed minesweepers are vulnerable if they try to clear lanes near shore without destroyer escorts and no one has explained why large unarmored LCACs (below) will not be sunk trying to shuttle material ashore from ships safely at sea. Another problem is moving fuel, which accounts for more than half the cargo needed ashore. In past invasions, hoses were run from ships just off the beach and fuel pumped to bladders ashore. Running a hose 20 miles offshore is impossible, but this problem is ignored. (The simple solution are Bunker Barges.) Finally, despite the communications revolution, marines ashore still rely on small radios with ranges too limited to reliably communicate with Navy ships "over-the-horizon."

Several studies have proven over-the-horizon invasions impractical, including one

from the Naval War College: "Logistical

Implications of Operational Maneuver From the Sea," which concludes:

"...the

Navy and the Marine Corps need to keep the laws of logistics in mind if they are

to distinguish campaign plans from fanciful wishes." An Amphibious Probe or

Amphibious Demonstration can be

launched from over-the-horizon elsewhere to confuse an enemy. Over-the-horizon landings can work for a small

Amphibious Seizure, but

will prove disastrous for an Amphibious Invasion.

Several studies have proven over-the-horizon invasions impractical, including one

from the Naval War College: "Logistical

Implications of Operational Maneuver From the Sea," which concludes:

"...the

Navy and the Marine Corps need to keep the laws of logistics in mind if they are

to distinguish campaign plans from fanciful wishes." An Amphibious Probe or

Amphibious Demonstration can be

launched from over-the-horizon elsewhere to confuse an enemy. Over-the-horizon landings can work for a small

Amphibious Seizure, but

will prove disastrous for an Amphibious Invasion.

The objective in an Amphibious Invasion is to RAPIDLY seize a port for larger follow-on forces before the enemy can react to the surprise. This requires that mines be removed beforehand and coastal threats silenced quickly. Over-the-horizon operations are excellent for raids and useful for the initial landing of marines as part of an Amphibious Invasion to identify and destroy most coastal gun and missile batteries. However, once that has been accomplished ships must move close to shore to off-load the landing force quickly while warships instantly engage surprise threats with direct naval gunfire and provide indirect fire support for marines attacking inland.

Navy surface combatants must approach the shore and FIGHT emerging threats. There is no guarantee that all mines have been removed or that all missile and gun batteries have been destroyed after the first wave of marines land from over-the-horizon and search for threats. In some cases, lightly armed marines are unable to destroy all coastal threats and destroyers must come to the rescue and engage enemy coastal weaponry directly. Small enemy boats or submarines may appear from nowhere to attack approaching ships. Before the vulnerable amphibious ships, fuel tankers, and cargo transports approach shore, the Navy must send escorts "in harm's way," just as they have done in every Amphibious Invasion, which last occurred in 1950.

Heavily armored battleships were ideal for this role since they could withstand a dozen heavy hits and directly blast threats with 16-inch guns. They were retired so the Navy must send in unarmored warships and hope for the best. This means that sailors may suffer casualties and that ships may be sunk, but that is part of war. If land forces are suffering a thousand casualties a week, the loss of a few hundred sailors during an Amphibious Invasion to win a war must be accepted. If landward alternatives are not available, a difficult Amphibious Invasion is the only option as was often the case during World War II. The Allies lost a dozen warships off the coast of Normandy to mines and shore fire while invading France in 1944 (below) as army divisions quickly invaded and had 100,000 troops ashore with heavy armor before Hitler ordered a counterattack.

In 1945, planners concluded that the Japanese island of Okinawa must be seized because there was no landward path to Japan. This became the bloodiest battle in the history of the US Navy in which 5000 American sailors were killed and 38 US Navy ships sunk during attacks by thousands of precision-guided munitions, called kamikazes. Several battleships were hit but suffered no serious damage. Most of the losses were US Navy destroyers that boldly set up a screen to protect the landing force where they fought, died, and helped win the battle.

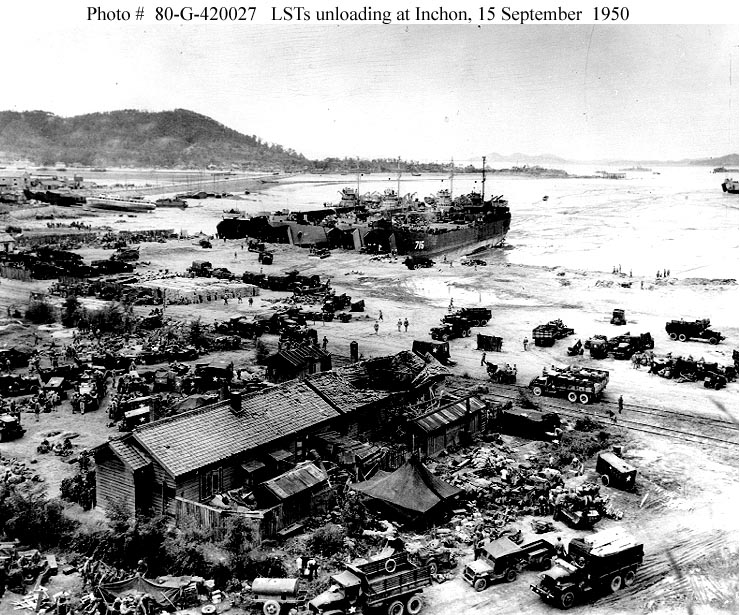

The very successful 1950 landing at Inchon, Korea provides an excellent example of an Amphibious Invasion. The port area was swept for mines as six Navy destroyers anchored off Wolmi-Do and began firing pointblank at targets there and along the Inchon waterfront. Their bombardment continued for about an hour followed by heavier gunfire from cruisers and more air attacks. North Korean return fire damaged three of the destroyers, killing one officer. Wolmi-Do and other nearby targets were hit again the following day, with good results, and again just before landings began on the morning of 15 September. (US Navy warships often fired on coastal targets so these attacks did not reveal the landing plan.) Marines seized the port of Inchon the first day to allow ship transports to land follow-on forces. This allowed the US Army's X Corps to quickly disembark and push rapidly inland to trap and destroy most of the North Korean Army fighting in southern Korea before it could withdraw northward.

A similar over-the-horizon invasion at Inchon using OMFTS would have allowed Marines to seize the amphibious objective area after several days of difficult fighting without naval gunfire support, and because the delay of waiting for armored vehicles and supplies to be shuttled ashore from distant ships. Several LCUs, minesweepers, and numerous amtracks would have been destroyed by shore fire until aircraft suppressed the threat, while destroyers lingered safely offshore. Meanwhile, X Corps would have to wait a week to move ashore as the North Korean forces shifted northward to contain the landing.

Accepting the OMFTS doctrine, which allows Navy warships to hide offshore, is a bad idea. Marine amtracks would become ducks in a shooting gallery if they approach shore without cover fire. During an interview about the 1944 Normandy landing published in the book "The German Generals Talk", German Field Marshall von Rundstedt said: "Besides the interference of the Air Forces, the fire of your battleships was a main factor in hampering our counter-stroke. This was big surprise, both in its range and effect." German General Blumentritt remarked that US Army officers who interrogated him after the war did not seem to realize what a serious effect naval bombardment had on German defenders. Without naval gunfire support in the future, numerous amtracks and LCACs will be lost to mines if unescorted minesweepers cannot approach shore.

Attempting to shuttle cargo from ships 20 miles offshore takes at least five times longer even with fast LCACs. In addition, well-deck operations are difficult in mildly rough seas and LCACs can't hover well in white-cap waves. However, ships that move into a protected bay have less problems with difficult seas and offloading five times faster allows them to depart the dangerous combat area much sooner. Moreover, there are rarely enough ships to embark the entire landing force along with needed supplies so amphibious and cargo ships must off-load quickly and return to the regional staging area to embark more troops, equipment, and supplies. The idea of "seabasing" to deliver items just when needed seems attractive, but this ties up shipping and exposes ground forces to extreme risks since weather, confusion, and enemy action can disrupt an offshore supply chain.

Ask any OMFTS advocate to explain how the 1944 landing in France would have worked with such a tactic today. Soldiers in helicopters could have landed in France, but why? Three divisions of paratroopers were landed over-the-horizon in France but they just hung on for several days until rescued by units arriving from the sea. This wasn't because they were dropped wrong, but because they lacked firepower and quickly attracted enemy forces, which made aerial resupply too dangerous. Modern heavy-lift helicopters are impressive, but landing to resupply units engaged in heavy combat with modern forces is foolish, especially after enemy units surround the landing zone.

Sea-based amphibious operations are ideal for counterinsurgency and this may explain why they appealed Vietnam-era Generals. However, transport helicopters cannot operate safely over areas occupied by a well-equipped enemy for days at a time as they did in South Vietnam and Iraq; and dragging external cargo inland at just 50 knots over enemy territory will prove suicidal. The biggest advocates for this flawed doctrine have been military contractors eager to sell ultra-expensive transports. In the December 2001 issue of Naval Proceedings, Marine Corps Major Chris Wagner from the Strategy Center at Headquarters Marine Corps revealed: "The OMFTS concept was developed to create tactical synergy through integration of forces afloat and ashore, and it was instrumental in justifying major acquisition programs such as the advanced amphibious assault vehicle and the MV-22 Osprey."

Adopting a flawed OMFTS doctrine has

already led to disastrous decisions. The key ship for an Amphibious Invasion is the

Landing

Ship Assault that can beach to allow

all its vehicles to drive off its ramp within minutes. Unfortunately, all 27

of the US Navy Newport

class LSTs (left) were decommissioned in the 1990s with half their service life remaining. The mighty US Navy/Marine Corps

and Navy/Army teams that conducted dozens of large amphibious invasions

during World War II have faded into history.

Adopting a flawed OMFTS doctrine has

already led to disastrous decisions. The key ship for an Amphibious Invasion is the

Landing

Ship Assault that can beach to allow

all its vehicles to drive off its ramp within minutes. Unfortunately, all 27

of the US Navy Newport

class LSTs (left) were decommissioned in the 1990s with half their service life remaining. The mighty US Navy/Marine Corps

and Navy/Army teams that conducted dozens of large amphibious invasions

during World War II have faded into history.

The US Navy has a force of 33 huge, expensive, vulnerable, and inefficient "amphibious" ships that cannot safely operate within a hundred miles of an enemy coast. Most of their design is wasted with well decks filled with landing craft and hangar decks filled with helicopters to act as "connectors" to shuttle men and material ashore. These expensive, vulnerable, and unarmed connectors add no combat power and cannot safely operate within a twenty miles of an enemy coast because they are easily destroyed by precision guided guns and munitions. These problems exist because the US Navy's amphibious fleet is no longer amphibious, but devolved into huge, comfortable cruise ships designed to operate in safe seas for extended Third World police missions.

Today's American amphibious forces are unable to conduct invasions since they adopted a doctrine suited to small raids and minor seizures. There are seven types of amphibious operations, and the proven World War II doctrine for an Amphibious Invasion remains valid. American amphibious forces will remain dysfunctional until this is understood and a hundred Landing Ship Assault (a modern LST) are procured.

Invasion Preparation

Before any major amphibious invasion, an amphibious task force must assemble while follow-on forces and months of supplies are moved into theater, which often requires the construction of numerous base camps. Local air and naval superiority must be established. Land-based aircraft may accomplish this task if airbases are available, otherwise Carrier Strike Groups are needed.

Airborne and helicopter-borne forces can play no combat role in amphibious operations against an opponent with modern weaponry, as explained elsewhere in this book. Advancements in anti-air weaponry along with sharp cost increases for modern combat transport aircraft have made the idea absurd, although it persists in corporate sales pitches. One example are ridiculous concepts for using V-22 tiltrotors to fly troops far inland as part of an amphibious invasion. Most would be shot down during their first sortie while the isolated and unsupported infantry are soon overrun. Transport aircraft are valuable to move troops from staging areas to ships offshore, but must remain far from enemy air defenses.

The primary goal of any amphibious invasion is to seize a seaport to quickly offload follow-on forces to exploit the surprise offensive and press inland. This idea is alien to US Marine Corps doctrine based on its World War II concept of amphibious seizures of small islands. This is why the use helicopters and LCAC hovercraft to land on remote undefended beaches is ridiculous. What is the point of landing in a marshy area miles from a road where ships cannot dock to off-load follow-on divisions to continue the offensive inland? During World War II, the Germans knew ports were key and focused their defenses around French ports and left much of the French coastline nearly undefended.

If the Allies wanted to invade a remote beach with no nearby port, they were welcome. The Allies proved crafty and came up with a novel idea to build two huge "Mulberry piers" in England, and float them across the channel so ships could dock and off-load directly at the relatively lightly defended Normandy beaches. This concept is unlikely to work for future amphibious invasions unless they take place across a channel, so port seizures remain the focal point of amphibious invasions. The 1950 amphibious invasion of Inchon in Korea was a direct seizure of a port. It was lightly defended by North Koreans because they thought tides and the high walls would deter a risky attack there. US Marine Corps Generals opposed the landing for those reasons, but were overruled by Army General Douglas MacArthur who often favored the unexpected.

It is possible to off-load ships without piers or where coastal waters are too shallow for large ships, which is called Logistics Over-the-Shore (LOTS). The US Army maintains this capability, details can be found a this link: Army Watercraft However, after amphibious forces have cleared the beach it takes a couple days to assemble causeways and get this system working. LOTS offloads are a very slow process that leaves ships vulnerable while sitting offshore and bad weather can disrupt operations. Given the logistical consumption of modern ground forces, the US military would struggle to maintain just one heavy division in combat with all the US Army's LOTS resources committed in support.

As a result, a port seizure is the goal for a major amphibious invasion. If an enemy is weak, ill-trained, or in disarray, they may not even guard a port. He may focus defenses at a major airport and several wide beaches where they assume an amphibious force may land. Even if a port is guarded, it may be just a dozen infantrymen. In such cases, LCUs full of tanks and troops can come over-the-horizon at night and seize the port entrance and piers, perhaps preceded by commandos. The nearby town can be quickly overrun while ships arrive at the piers at dawn and begin to unload. The enemy commander would be stunned because no one thought a landing force would simply cruise up to piers at a port and unload like cargo ships delivering goods.

The idea

of sending LCUs over-the-horizon at night full of tanks and troops has many

applications. They don't look like warships, more like coastal

barges. They are slow with a low profile, yet can carry three heavy tanks

or 400 troops. Everyone thinks of helicopters for amphibious raids or

rescue operations. However, helicopters are loud and attract

gunfire. An LCU (right) can blend in with coastal water traffic and put troops and

tanks ashore in a city to conduct a raid or embassy rescue before local warlords

realize what is happening. They are bullet proof, mount .50 caliber

machine guns, are all-weather, and cannot be shot down.

The idea

of sending LCUs over-the-horizon at night full of tanks and troops has many

applications. They don't look like warships, more like coastal

barges. They are slow with a low profile, yet can carry three heavy tanks

or 400 troops. Everyone thinks of helicopters for amphibious raids or

rescue operations. However, helicopters are loud and attract

gunfire. An LCU (right) can blend in with coastal water traffic and put troops and

tanks ashore in a city to conduct a raid or embassy rescue before local warlords

realize what is happening. They are bullet proof, mount .50 caliber

machine guns, are all-weather, and cannot be shot down.

Clearing the Landing Area

It is amazing that large navies do not maintain a detailed database of every port, pier, and beach in the world. Expensive ships continually chart the ocean so that submariners have good data. It will cost little to send agents on vacations around the world to take soil samples of beaches to determine if they are passable by wheeled and tracked vehicles. They can measure beach gradient to see how steep they are, estimate harbor depth if not publicly known, take photos of likely defensive positions and current military positions, and take GPS readings. This is not illegal, they are just tourists interested in scuba diving. This is a good weekend mission for military attaches stationed at embassies abroad. All this can be done in peacetime so fewer dangerous reconnaissance missions are required during wartime.

If an enemy is well organized and led by capable officers, ports will be strongly defended so a direct seizure is impossible. Ports are usually in urban areas protected by sea walls and jetties, so they are easy to defend. Therefore, capturing a port from the landward side is usually required. It may be possible to land a force by helicopter a few miles from a port if anti-aircraft defenses are minimal, but such a force cannot include tanks, so attacking into an urban port area would be difficult, unless heliborne Rhinos are used. Landing on a beach remains the best option, so detailed reconnaissance is required.

Nevertheless, wartime requires reconnaissance teams to scout potential landing sites for mines and enemy forces. They can be safely inserted and extracted at night by stealthy DE corvettes. Corvettes can escort minesweepers and scout for enemy positions and may become involved in firefights. If coastal submarines or small attack boats are present, they hunt those while friendly aircraft circle offshore waiting to assist. Aerial and signal intelligence reconnaissance is important as well. Prior to an amphibious invasion, commanders may launch amphibious raids or probes to test enemy defenses and reactions. Corvettes hope that shore-based missile sites open fire to expose themselves for destruction, while their small size and CWIS should allow them to survive.

Once an invasion point is selected and the amphibious force assembled and in transit, the attack can begin. Cruise missiles launched from ships attack known high-value targets in the amphibious objective area while destroyers and cruisers armed with 8-inch guns pummel coastal defenses from 20 miles offshore. This distance is "over-the-horizon" so that enemy shore batteries cannot use shore-based radar to target them due to the curvature of the Earth. Commandos landed by stealthy DE corvettes the previous night attack targets and help guide aircraft bombing while spotting naval gunfire rounds. Jet aircraft search for and attack suspect targets. Bridges may be destroyed or seized by commandos depending on the plan for landward operations. Heavy bombers arrive and carpet bomb the landing area to destroy enemy precision guided weapons systems that evaded detection.

The general location of enemy combat units should be known, so bombers arrive to carpet bomb areas where enemy units are thought to exist. This is the substitute for the pre-invasion naval bombardment by battleships, although naval gunfire from 8-inchers will help. Meanwhile, entire squadrons of corvettes approach shore and challenge shore batteries to duels while commandos check the surf and disarm shallow water mines. Deception is still a factor at this point. Amphibious Raids may be made at other possible landing sites to confuse the enemy. Amphibious Demonstrations may be conducted elsewhere.

The Landing Force Arrives

A few hours before the actual landing, the bait ship returns for a final check, but this time a real destroyer will shadow her for protection to support the landing. Fire support positions are set up offshore. It may be possible to land howitzers on tiny offshore islands, or AAV-Ms with 120mm mortars beach on sandbars or reefs or tiny islands and standby to fire. At dawn the first wave arrives in the form of LCU Gunboats launched from 20 miles offshore. The LCU's tanks open fire some 2000 meters offshore and pummel enemy defenses with direct 120mm tank fire and hopefully draw fire from shore batteries that withheld firing at the corvettes because their wise commander ordered them to only fire at amphibious landing craft. Some LCU gunboats carry C-RAM anti-missile systems whose 20mm gatling guns help provide a defensive shield. If heavy enemy shore fire is encountered, cruisers and destroyers move a few miles closer to shore and use their counter-battery radar to locate and destroy enemy mortar and artillery positions.

Corvettes move close to shore and engage enemy targets from behind the LCU gunline. However, they may be forced to retreat offshore if intense enemy fire damages or sinks several of these small ships. LCUs may be sunk, but it is easy for everyone onboard to safely escape. Small boats from larger ships offshore that escorted the LCUs rescue crews from any sinking LCU or corvette. Attack helicopters join in the attack, staying offshore and out of heavy machine gun range while employing long-range Hellfire missiles.

Less than an a hour after the LCU tanks began firing at targets ashore, one or two bait ships appear. These old, stripped destroyers zigzag toward shore to entice shore batteries that have withheld their fire for larger ships. These may be missile batteries several miles inland with forward observers along the coast. If shore fire is light, the bait destroyers slow and present a big radar reflecting broadside near shore in hopes of attracting fire. They open fire with their CWIS to encourage return fire. If bait destroyers are quickly sunk by a surprise barrage of anti-ship missiles, the invasion may be delayed or called off.

If all looks well, amphibious ships move near shore and begin to off-load their amphibious vehicles "amtracks" and other equipment. The exact distance depends on local terrain and coastline. As the amtracks reach the LCU gunline, the LCUs attack abreast with the amtracks while AAV-AAGs and LCUs with C-RAMs gun down threats. As the tanks and amtracks hit the beach they are supported by Amtrack Variants firing 120mm mortars and autocannons. As they land, larger LSAs arrive and beach themselves to disgorge more tanks and troops. As forces move inland, cruisers and destroyers move closer to shore to keep their guns in range of advancing forces and reduce response time.

With DE corvettes,

LCU

gunboats, and LSAs with 5-inch guns to provide direct firepower, while bait ships provide further

assurance that anti-ship missile batteries are not a threat, large amphibious

and cargo ships can now move close to shore to off-load. This brings into question the value of expensive LCAC

hovercraft, which are not bulletproof and cannot carry nearly as much as an LCU

of the same size. LSAs are even better since they can move cargo from

regional staging bases directly ashore. Offloading ashore also eliminates the need for

LCACs and a new amtrack

that must cruise at 25 knots in the water to come from 20 miles

over-the-horizon. Such an amtrack is under perpetual development by the US Marine

Corps because it is impossible to construct.

With DE corvettes,

LCU

gunboats, and LSAs with 5-inch guns to provide direct firepower, while bait ships provide further

assurance that anti-ship missile batteries are not a threat, large amphibious

and cargo ships can now move close to shore to off-load. This brings into question the value of expensive LCAC

hovercraft, which are not bulletproof and cannot carry nearly as much as an LCU

of the same size. LSAs are even better since they can move cargo from

regional staging bases directly ashore. Offloading ashore also eliminates the need for

LCACs and a new amtrack

that must cruise at 25 knots in the water to come from 20 miles

over-the-horizon. Such an amtrack is under perpetual development by the US Marine

Corps because it is impossible to construct.

In summary, a modern Amphibious Invasion would be almost like those in World War II. Major differences are that bomber aircraft substitute for battleships to unleash massive area firepower at enemy unit locations. Cruise missiles fired from ships and aircraft can destroy high-value targets ashore. Enemy precision-guided munitions are a major threat, so stealthy DE corvettes and small LCU gunboats fill the destroyer's direct fire role, while today's larger, expensive cruisers and destroyers provide indirect fires from a distance with targeting help from counterbattery radar. Tanks were carried by LCUs during World War II, but their lack of a stabilized main gun made employment impractical, while their firepower and accuracy was far, far less effective than today's tanks. Attack helicopters can provide additional fire support. Bait ships are insurance that no major anti-ship systems remain hidden before vulnerable amphibious and cargo ships approach shore to off-load as quickly as possible.

Moving Inland

At this point, warfare becomes a land battle after the landing force secures a seaport using tactics discussed in other chapters. Helicopter forces may have landed as blocking forces depending on the terrain and the enemy air defense threat, as discussed in Chapter 7. If securing a port is not possible, follow-on forces and supplies can be off-loaded using LSTs and LOTS but this is a very slow, and inefficient process. After unloading, amphibious and cargo ships depart quickly to avoid enemy attack and pick up follow-on forces staged in theater; they do not linger off-shore full of supplies as part of an impractical seabasing concept. Enemy forces may fire cruise missiles or large ballistic missiles at the beachhead, as the Germans did with V-1s and V-2 at Normandy in 1944. Navy destroyers offshore and C-RAMs at the shoreline are capable of destroying missiles, although some will cause damage, and the war goes on.

©2015 www.G2mil.com